If Europe is really to be fit for the digital age, what should most concern policymakers is not the fate of cutting-edge start-ups but rather the long tail of conventional companies that have failed to digitalise. So far, its budget allocations have not reflected this challenge, but the new Multiannual Financial Framework and Resilience and Recovery Facility are an opportunity to rectify this. Policymakers often lament Europe’s poor digital performance. They bemoan the lack of companies with a scale and success like Google or Apple, and seek to foster digital companies that can rise to the challenge of US or Asian giants at the technological frontier.

It is important to remember, however, that most economic and productivity growth comes from the adoption of new technologies by existing firms, as they adapt and repurpose their business models to take advantage of said technologies. Part of this process of adaption is the start-ups that policy desperately wants to encourage. But more often than not, it is existing businesses that restructure to reap the productivity improvements.

This is where Europe has truly lagged. The

failure to reap the productivity benefits of the ICT revolution is responsible for much of our economic underperformance relative to the US. And yet EU policy, even when ostensibly targeted at improving our economic competitiveness, has in practice neglected the issue. As we enter a new budgetary cycle and begin to allocate RRF funds, policymakers must focus more of their efforts on digital adoption and catch-up.

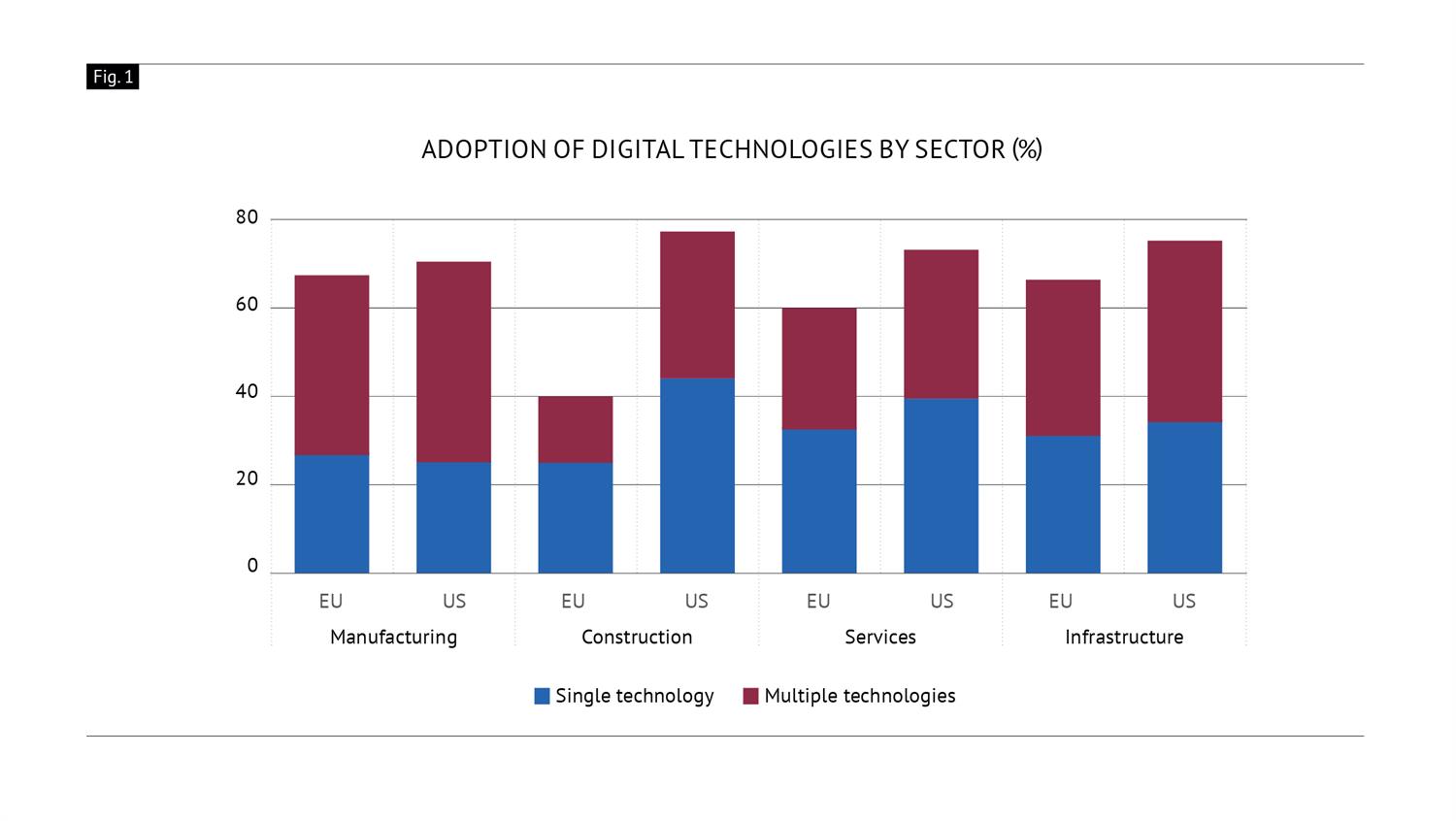

The current state of European firmsFigure 1 shows how EU companies lag behind their US peers. Overall, European firms have long

underinvested in digital assets and the associated intangibles (e.g. organisational change, training, management). The European Investment Bank’s (EIB)

latest Investment Report states that while US investment growth pre-pandemic was driven by equipment and intellectual property, half of Europe’s investment was accounted for by buildings and structures.

The EIB survey report also reveals that a greater proportion of EU firms are ‘leading innovators’. It is in the long tail of firms that adapt and adopt existing innovations that Europe lags. The lack of Googles is a problem, but not our main one.

As one would expect, the severity of the problem

varies between member states. 27% of EU companies had high digital intensity in 2019, but in Denmark, the figure was 53% compared to 10% in Romania. But this is not a simple story of ‘East versus West’ or ‘North versus South’. In Germany, the figure was 28%, while France was below the EU average, at 24%. Neither is this a phenomenon restricted to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – although they are by far the worst performers. Across all sizes, EU firms are less digital than US firms, and around 25% of large firms in the EIB’s survey report have not digitalised.

What is impending EU firms from digitalising?Two key market failures keep EU firms from digitalising, besides

underinvestment in digital infrastructure. On the one hand, much of the required investment is intangible and does not create the collateral required by banks. As a result, such projects are

critically underfinanced.

On the other, digitalisation is hampered by a lack of skills and knowledge and poor management practices. The latter is, if anything, a greater impediment, as firms are unaware of the potential of digitalising. Even when digital technologies are adopted, successfully incorporating them means adapting business models. Poor managers use digital tools poorly, in SMEs and

multinationals alike.

These problems are likely to be compounded by the COVID-19 shock. Although the pandemic increased awareness of digitalisation, overall private investment has plummeted. The EIB report predicts a cumulative drop of €831 billion in 2020 and 2021, and digital and intangible investments will be caught in the storm.

What has the EU been doing up until now?Many factors can drive these market failures, although

targeted programmes can overcome technological and managerial gaps. Nevertheless, the EU’s efforts have been critically underfunded.

Until recently, the EU’s flagship policy programme was the

Digitising European Industry (DEI) initiative. It made use of Horizon 2020 funds to support hundreds of Digital Innovation Hubs (DIHs), to overcome the knowledge gaps amongst SMEs, and various research projects. Nominally, €5 billion was allocated – €500 million for the DIHs and the remaining for the research projects. In reality, much of this funding was already committed, and many projects predated the DEI. The projects were also primarily dedicated to R&D, which does little to address the adoption challenge outlined above.

The DIHs appear to have been effective once used, but only reached around 0.01% of European SMEs. 57% of SMEs

surveyed by the EIB were unaware of their existence, or of any national/EU digitalisation programme. DIHs also have the smallest presence in EU regions that lag the most in digital uptake.

Furthermore, the Court of Auditors reports that the Commission did not actively encourage member states to allocate European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) to the DEI. Overall, only 6% of European Regional Development Funds were used on

digital projects, of which only around 10% appear to focus directly on

SME digital adoption. In contrast, the funds allocated to more general SME support were six-fold. Looking at other EU funding streams, only 9% of the European Fund for Strategic Investment was spent on

digital projects.

These figures may undercount the support given to digital projects if some are recorded as SME or R&D support. However, the fact that COSME, an EU programme dedicated to SME finance,

only launched a pilot for digital projects in 2019 indicates that digital adoption has not been its focus over the 2014-20 funding period. Another telling indicator is that the EIB Investment Report identifies ESIF as the driver behind the high investment rate in buildings and structures, in contrast to the equipment and intellectual property that dominate US investment data.

As

US President Biden once said, “Don’t tell me what you value. Show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.” Closing the digital gap amongst private firms – widely considered the key reason for European economic underperformance – appears to have been one of the EU’s lower-ranked priorities.

A Europe fit for the digital age?Europe’s policymakers have rightly determined that the COVID-19 recovery must place the EU on a more sustainable and competitive economic trajectory. But Europe’s economic competitiveness problem, whether SMEs or large firms, is in large part a digital adoption problem. Will the allocations of the Multiannual Financial Framework and NextGeneration EU package reflect this?

The

Digital Europe programme allocates €580 million to boost digital skills and €1.1 billion for digital adoption across society, including €750 million for DIHs. While it may help at the margin, it is not a particularly meaningful sum given the scale of the problem. The Horizon funds address a fundamentally different policy problem.

InvestEU’s allocation for SMEs, research, innovation and digitisation was cut from €20 to €13.5 billion. As a financial guarantee, it can mobilise a large multiple of additional investment, but will have to cover a range of policy initiatives beyond business digitalisation.

Facing both limited resources and the task of restructuring the world’s largest economy, the EU must pick its targets carefully. Unless a significant proportion of the funds available are used to tackle the key market failures (via infrastructure upgrades, technology transfer programmes, skills and management training, and finance guarantees), the EU’s economy will continue to lag behind its peers.

In practice, this means that ESIF and the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) – by order of magnitude, the most well-funded EU industrial policy levers – should be directed to this task. The multitude of EU-funded SME and company support programmes must develop a specific digital focus to incentivise firms to digitalise. The Commission will also have to ensure that a significant proportion of RRF digital spending addresses these issues, even if it is at the expense of investments in cutting-edge projects. For now, catching up should be the EU’s priority.

Frederico Mollet is a Policy Analyst in the Europe’s Political Economy programme.The support the European Policy Centre receives for its ongoing operations, or specifically for its publications, does not constitute an endorsement of their contents, which reflect the views of the authors only. Supporters and partners cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.