As energy ministers meet in Brussels for an emergency meeting on Europe’s energy crisis, we review potential measures to bring down electricity and gas prices and help Europeans face the winter. Zero Russian gas became Europe’s central scenario for this coming winter when Russia announced this week that it would halt Nord Stream 1 operations. Gas futures have reached €240 per megawatt-hour (MWh), and electricity prices have

peaked close to €700 /MWh. Since records broke in late August, a political consensus has formed across Europe that the current price levels are untenable. Gloomy economic forecasts and protests in Prague last weekend hint at what might be in store if Europe cannot turn prices around and halt the impending cost-of-living crisis.

Member states have announced

an array of national market intervention and support measures over the past weeks. Tomorrow afternoon, EU energy ministers will meet in Brussels to agree on an EU-wide response. The European Commission pre-announced a

5-point plan to boost energy savings, cap and redistribute windfall profits, bail out energy utility companies and curtail Russian gas prices. Here, we propose 8 political and economic considerations to help frame the ongoing discussions.

SUBSTITUTION, SAVINGS AND SOLIDARITY

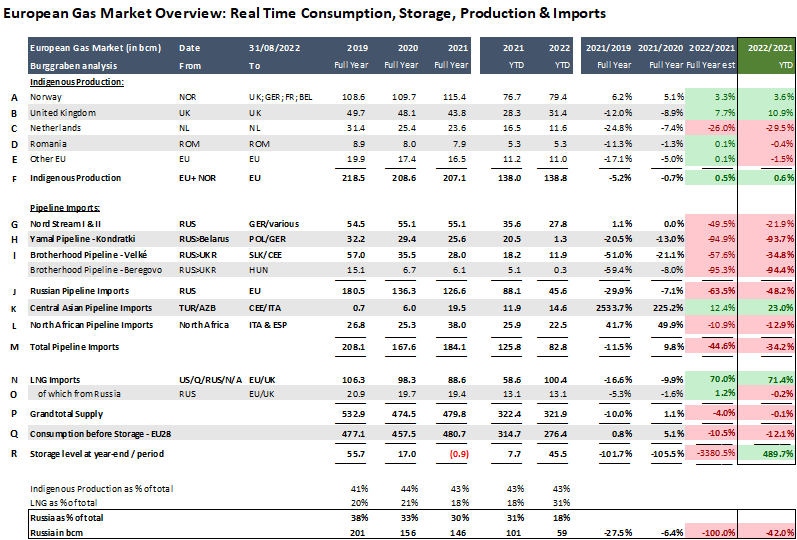

1. Short-term alternatives to diversify supply have been largely exhausted Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the EU has acted resolutely to diversify its energy mix away from Russian coal, oil and gas. Europe’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports have risen by 70%, and Russia now provides only 9% of the EU’s imported gas, down from 40% pre-invasion.

Source:

Alexander Stahel (2022) In 2023, new LNG capacity will be key to replacing the roughly 125 billion cubic metres of pipeline gas that Russia delivered to Europe in 2021. In the medium term, much more will undoubtedly have to be done on the supply side to bring down prices, deliver the transition to renewables and build Europe’s energy security. But in the short term, supply-side alternatives have been largely exhausted. The EU’s next logical move is to act more decisively on demand, as well as explore measures to intervene in market mechanisms and prices.

2. Europe needs coordinated demand reduction and pandemic-style measures We still see a significant need and potential for demand reduction. In July, the European Commission’s

15% demand reduction plan was a good start, allowing a consensus to form across the bloc. National capitals have also come up with useful ideas, but now more needs to be done. Current gas savings stand at 12% year to date. Subject to weather and import capacities, Europe must save up to 20% year on year, with even greater efforts required in some member states.

Further demand reduction will require cross-societal efforts and possibly rationing and ‘pandemic-style’ measures, such as mandatory teleworking. In addition to efforts across industry, reducing the energy consumption in public and corporate institutions and private housing are effective and necessary measures. It also presents the EU with an opportunity to push ahead with reducing CO2 output of European households through energy efficiency measures, like heat pumps. The cheapest energy Europe will ever get is what

it doesn’t use.

3. An EU-level fiscal instrument could help deliver efficient burden-sharing Policymakers must ensure that those who can carry a greater share of the burden do so to benefit those worst hit. Not leaving anyone behind is not only

a matter of solidarity but also an important means to contain economic and political ripple effects. This applies nationally, of course, where redistributive policies will be paramount, but also at the European level.

The European Commission has floated the idea of compensating member states making efforts benefitting others. Spain, in particular, could be

a shock absorber thanks to its renewable, pipeline and LNG potential if interconnections are developed. In a twist of fate, this would turn the tables of the dependencies of the eurozone crisis, making Germany and other Northern and Central European states beholden to their southern neighbours, who are less exposed to Russian gas. Sure, compensation mechanisms are not easy to design and will encounter political obstacles. But for Europe, the risk is an inadequate and inefficient crisis response overall. We therefore believe there is a strong case for an EU-level fiscal instrument inspired by the current Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). Financed through debt and contributions according to a key reflecting dependence on Russian energy, an ‘energy security fund’ should back significant suppliy and demand efforts across Europe. The RRF precedent suggests it will not happen overnight, but that it can be done.

ELECTRICITY 4. Emergency market reform should not decouple electricity prices from fossil fuels The dramatic surge in electricity prices has highlighted a weak spot in today’s electricity market design, where price levels are set by the marginal cost of the most expensive source – which now is natural gas. The EU is right to put market reform on the table to ensure better crisis resilience.

But we advise against hurrying into reform along the so-called

Greek proposal, consisting of a new price-setting mechanism for renewables, hydropower and nuclear electricity. Unlike fossil fuel prices, it is extremely difficult to determine the price for renewable energy: once launched, renewable energy plants (e.g. wind farms) have hardly any operating costs. The coupling with other energy prices has become a proven system of pricing at levels above marginal cost. This remains key to ensuring sufficient investment in renewables and, ultimately, the success of Europe’s energy transition. The case of hydropower is also noteworthy: a variable market price is the necessary signal to adjust volumes efficiently according to market needs, allowing reservoirs to serve as ‘batteries’ in Europe’s electricity market. For other renewables, long-term contract models based on an estimate of total levelised costs might be a viable model to be explored. But in the current emergency we believe other solutions involving the contributions of the energy industry to be more feasible and faster to implement.

5. A levy on excess profits should be structured as a permanent market correction instrument We prefer what has been termed an ‘electricity price cap’ but is, in reality, a levy on excess profits. Different versions of this idea have been presented by the

Commission and member states such as

Germany and Austria. On this model levies on windfall profits on non-gas energy producers (e.g. renewables, nuclear power) are redistributed to consumers to reduce the electricity price. The advantage is that the current energy market model is left in place.

The renewable energy sector has voiced concerns that such a windfall tax could shake investor confidence and run counter to the goals of the green transition. But, if well designed, this should not be the case. Firstly, a levy should only be on profits, not revenues, as it could then be passed on to consumers and stir inflation. It should be based on a clear measure of excess profit, such as an amount above a specified return on capital. Secondly, the threshold for a levy should be high and only cover windfalls, which long-term investors do not usually expect to gain in any case. Thirdly, the EU should aim for a permanent instrument rather than ad-hoc measures. Automatic triggering of the levy at certain price levels as a relief valve in case of market spikes would provide a more predictable market and investment environment. Fourthly, the price cap should only apply to a measure of basic consumption, which would differ across member states or regions. This would guarantee that poor households are shielded from high prices while preserving strong incentives for all to consume less electricity.

GAS 6. The EU should act on the gas price but steer clear of the Iberian model

Acting only on electricity prices is no longer an option. However, we advise against a gas price cap, as is currently in place in

Spain and Portugal and which has been discussed in countries like Germany and the UK. Yes, an electricity price cap based on levies on non-gas producers does not help consumers who rely on gas for their heating. But this concern is outweighed by the disadvantages of a gas price cap.

As observed in Spain this summer, reducing the consumer gas price through state subsidies drives up consumption. In July, Spain recorded the highest ever gas consumption in its power sector, at 562 gigawatt hours per day. This runs directly counter to the goals of energy saving, carbon reduction and the green transition. Increased demand also leads to higher gas prices, which disproportionally benefit Russia and other autocracies.

Case in point, Spain is now one of the largest importers of Russian LNG. Finally, subsidies on gas lead to market distortions and inefficiencies. Over the past months, the gas price cap has made it profitable for Spanish operators to turn gas imports from France into electricity, then re-exported to France – a practice which is both highly uneconomical and at odds with the principles of the Single Market.

7. A price cap on Russian gas should be combined with the EU’s Energy Purchase Platform We believe there is a strong case for a gas price cap limited to Russia if done right. This can be justified as de-premium on unreliable energy supplies or as a sanctions-oriented instrument. A gas price cap would reduce Russian gas incomes but could also lead to Russia rejecting the cap and stopping deliveries altogether. A common European cap would make this more costly for Russia and preclude her from playing member states against one another.

A more sophisticated model would be the involvement of the

EU’s Energy Purchase Platform, which remains on paper for the time being. The Platform could be mandated to take over existing contracts with Russian energy providers and guarantee the implicated volumes to affected member states. Although a detailed legal assessment is needed, assigning contracts from European utilities to the Platform as a form of ‘bad bank’ of contracts which carry too much geopolitical risk would both address the current risks of default in the utility sector and give the EU more control over essential geopolitical interests. In order to guarantee the gas supplies currently covered by said contracts, the Platform would simultaneously have to buy medium and long-term volume commitments on the market.

8. A gas deal with Norway can deliver more energy security and lower prices Norway should be the first port of call for the EU’s Energy Purchasing Platform. The Scandinavian country is currently stretching its gas production capacities to the utmost in response to the energy crisis, and reaping exceptional windfalls. Its net cash flow from the

petroleum industry is estimated to surpass €100 billion in 2022.

Over a third of those revenues stems from the state’s direct ownership in oil and gas fields, known as the

State’s Direct Financial Interest. The mandate for the sale of state-owned gas – representing close to 30% of Norwegian exports – is set by the government and then handled by Equinor, a listed energy company. The current marketing instructions are to achieve the

highest possible overall value. In practice, roughly 50% of the gas is traded at spot prices and the remaining 50% sold as long-term volume commitments, typically running up to five years. There is, therefore, significant potential for Norway to sell more of its gas to the EU at rates cheaper than the market through long-term contracts. By changing the political mandate, Norway could choose to forego some sales at today’s record near-term prices in favour of long-term contracts, price certainty and a commitment to Europe’s energy security. This might also be the signal that will help push gas prices further down. As recently suggested by its

prime minister, Norway knows that its deepest strategic interest lies in Europe’s stability. No measure of short-term profit should eclipse that.

CONCLUSION Europe is facing a winter of uncertainty and discontent. None of the suggested measures alone will be enough to reduce electricity prices and secure the EU’s energy supply. Only by acting simultaneously on energy substitution, savings and solidarity can Europeans find a way out of this crisis. Friday’s Council meeting marks the beginning of many more rounds of discussions and measures. The next months will prove crucial to not only ensuring Europe’s collective energy security and paving the way for a more integrated and sustainable energy policy. They could also become, like crises past, a defining moment for Europe’s integration.

Philipp Lausberg is a Policy Analyst in the Europe’s Political Economy programme at the European Policy Centre.

Georg E. Riekeles is an Associate Director and Head of the Europe’s Political Economy programme at the European Policy Centre. The support the European Policy Centre receives for its ongoing operations, or specifically for its publications, does not constitute an endorsement of their contents, which reflect the views of the authors only. Supporters and partners cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.