SEE MORE

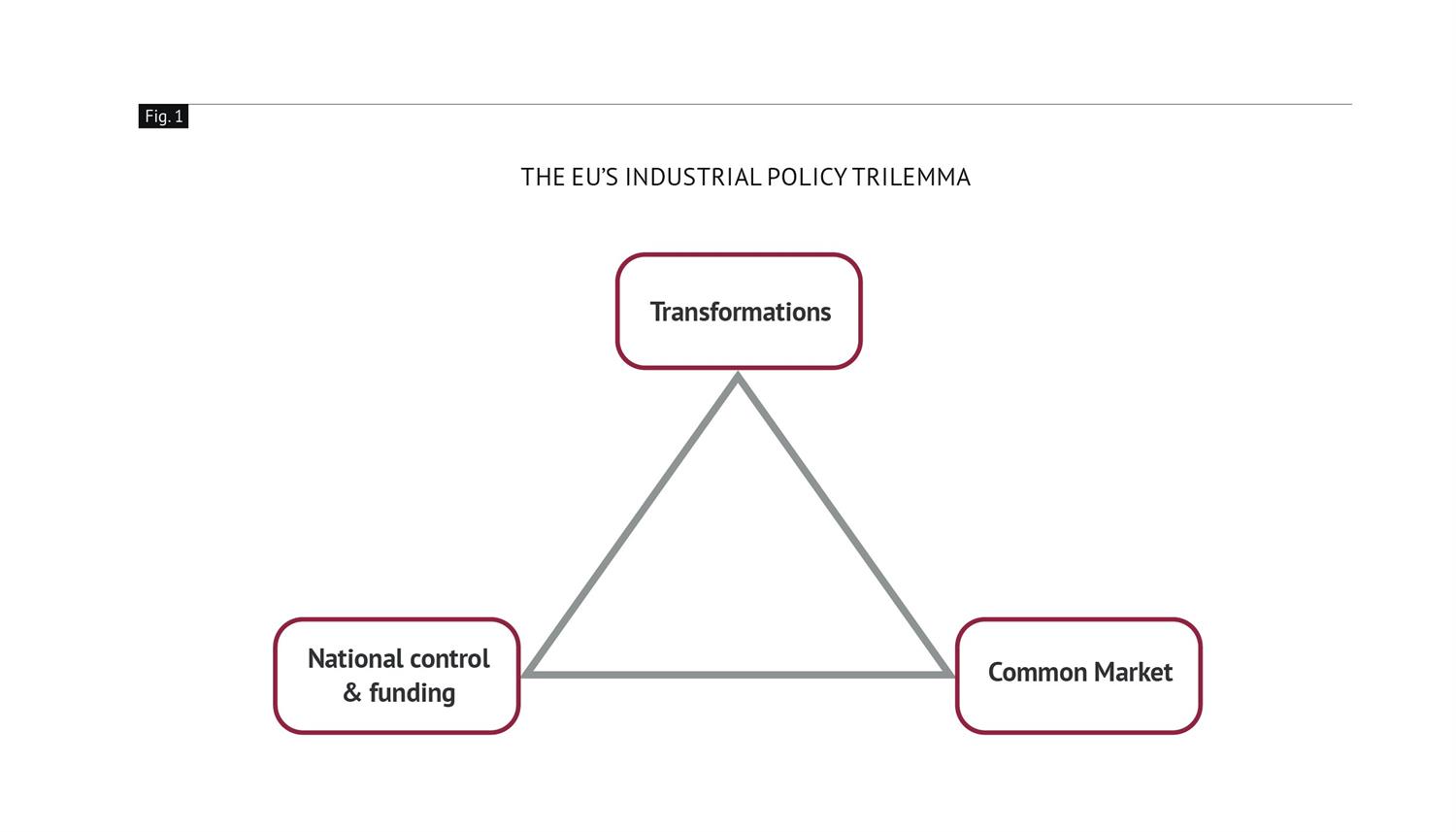

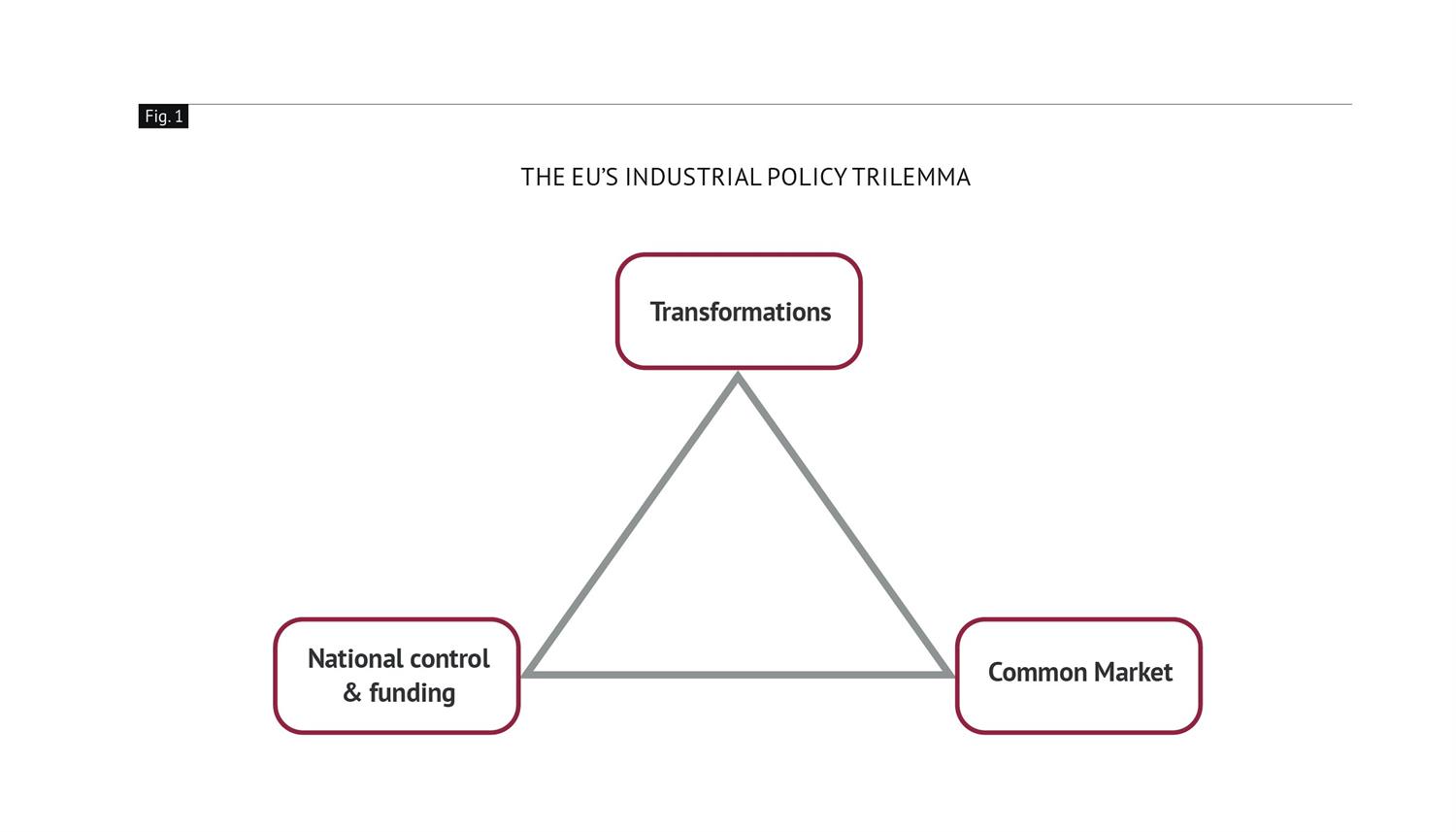

The EU is confronted with a conundrum: the industrial policy trilemma. European policy cannot achieve all goals at the same time: achieving the quadruple transition, maintaining the Single Market as well as national financing and control of industrial policy. Any two of these three elements can be combined but not all three. The EU will have to choose what must give in the end.

The quadruple transition as the EU’s main strategic priority

The quadruple transition – sustainability, technology, security, and demography – must be the EU’s main strategic priority. Without substantial progress in all of these fields, Europe will be unable to deal with climate change, compete in the global race for technological leadership, and preserve its prosperity and well-being in an increasingly challenging global environment. Giving up on the transformation goals is therefore not an option. But to achieve them, enormous amounts of (public and private) investment are indispensable. At the same time, governments will have to intervene to supply these public goods in the context of increasing interventionism across the globe, with China’s massive subsidies programmes and the American Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) being cases in point.

National control and financing of industrial policy undermines the Single Market

While transition targets and goals are being set at the European level (for example, in March, the EU presented the Green Deal Industrial Plan and the Net Zero Industry Act with concrete goals for green industry), financing and policy levers are largely left to the national level, which leaves the execution of industrial policy ultimately in member states’ hands. The consecutive liberalisation of state aid over the past crisis years has been the single most significant step to increase public financing of green industry, digitalisation, and strategic autonomy related initiatives such as the creation of large chips and battery factories. But, as the industrial trilemma stipulates, the quadruple transition and national control over industrial policy cannot be combined with a functioning Single Market, as these interventions inevitably distort the level playing field and limit the transformative investments to a small number of countries. The Single Market as the largest common market in the world, however, is essential for the EU’s competitiveness and important for achieving the bloc’s transition goals. Breaking this backbone of the EU economy is not something the EU can afford in times of permacrisis.

The need for a decisive EU industrial policy

If the EU wants to preserve the Single Market and successfully transform towards a greener, more digital, and economically and socially secure future, it will have to abandon national industry financing and control over industrial policy levers in favour of the EU level, pooling competences and funding, and providing strategic policy direction that acts in the European common interest. The EU’s current budget and its financing programmes such as Horizon, InvestEU, or the Innovation Fund are not sufficient to finance the ambitious transition goals, while the RRF is running out in 2026. The Commission’s recent Strategic Technologies for European Platform (STEP) proposal, which only includes €10 billion additional strategic investment, clearly does not alleviate this shortage in EU level funding. Member states will have to agree on something more decisive, including a substantive sovereignty fund, as initially stipulated by Commission President Von der Leyen last September, as well as exploring further permanent common borrowing to invest in the transformations. Providing sufficient EU level funding should be a top priority for the next Commission starting in 2024. The alternatives are spelled out by the industrial trilemma: abandoning either the Single Market or the quadruple transition. The EU can afford neither.

Fabian Zuleeg is Chief Executive and Chief Economist at the European Policy Centre.

Philipp Lausberg is a Policy Analyst in the Europe’s Political Economy programme at the European Policy Centre.

The support the European Policy Centre receives for its ongoing operations, or specifically for its publications, does not constitute an endorsement of their contents, which reflect the views of the authors only. Supporters and partners cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

The quadruple transition as the EU’s main strategic priority

The quadruple transition – sustainability, technology, security, and demography – must be the EU’s main strategic priority. Without substantial progress in all of these fields, Europe will be unable to deal with climate change, compete in the global race for technological leadership, and preserve its prosperity and well-being in an increasingly challenging global environment. Giving up on the transformation goals is therefore not an option. But to achieve them, enormous amounts of (public and private) investment are indispensable. At the same time, governments will have to intervene to supply these public goods in the context of increasing interventionism across the globe, with China’s massive subsidies programmes and the American Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) being cases in point.

National control and financing of industrial policy undermines the Single Market

While transition targets and goals are being set at the European level (for example, in March, the EU presented the Green Deal Industrial Plan and the Net Zero Industry Act with concrete goals for green industry), financing and policy levers are largely left to the national level, which leaves the execution of industrial policy ultimately in member states’ hands. The consecutive liberalisation of state aid over the past crisis years has been the single most significant step to increase public financing of green industry, digitalisation, and strategic autonomy related initiatives such as the creation of large chips and battery factories. But, as the industrial trilemma stipulates, the quadruple transition and national control over industrial policy cannot be combined with a functioning Single Market, as these interventions inevitably distort the level playing field and limit the transformative investments to a small number of countries. The Single Market as the largest common market in the world, however, is essential for the EU’s competitiveness and important for achieving the bloc’s transition goals. Breaking this backbone of the EU economy is not something the EU can afford in times of permacrisis.

The need for a decisive EU industrial policy

If the EU wants to preserve the Single Market and successfully transform towards a greener, more digital, and economically and socially secure future, it will have to abandon national industry financing and control over industrial policy levers in favour of the EU level, pooling competences and funding, and providing strategic policy direction that acts in the European common interest. The EU’s current budget and its financing programmes such as Horizon, InvestEU, or the Innovation Fund are not sufficient to finance the ambitious transition goals, while the RRF is running out in 2026. The Commission’s recent Strategic Technologies for European Platform (STEP) proposal, which only includes €10 billion additional strategic investment, clearly does not alleviate this shortage in EU level funding. Member states will have to agree on something more decisive, including a substantive sovereignty fund, as initially stipulated by Commission President Von der Leyen last September, as well as exploring further permanent common borrowing to invest in the transformations. Providing sufficient EU level funding should be a top priority for the next Commission starting in 2024. The alternatives are spelled out by the industrial trilemma: abandoning either the Single Market or the quadruple transition. The EU can afford neither.

Fabian Zuleeg is Chief Executive and Chief Economist at the European Policy Centre.

Philipp Lausberg is a Policy Analyst in the Europe’s Political Economy programme at the European Policy Centre.

The support the European Policy Centre receives for its ongoing operations, or specifically for its publications, does not constitute an endorsement of their contents, which reflect the views of the authors only. Supporters and partners cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.